Paisagem para Desaparecidos - Galeria Bruno Múrias. 2018

Galeria Bruno Múrias, Lisboa. 2018

A exposição começa em 1991. Aos vinte anos, Rui Calçada Bastos (Lisboa, 1971) faz uma viagem iniciática ao Tibete. Em 140km e nove dias, cruza os Himalaias Indianos para chegar à vida nova. Do episódio emergem algumas das peças (Paisagem para Desaparecidos II) que hoje apresenta, juntando-se a outras, para, assim, a tempos e cronologias distintos, darem forma a uma paisagem. E se a exposição o artista a concebe para hoje, é porque hoje é precisamente a condensação de um tempo inteiro que se evapora à medida que sucede na sua cadência própria, mas enchendo-se, no mesmo movimento, de uma misteriosa densidade. Paisagem para Desaparecidos é sobre a ausência.

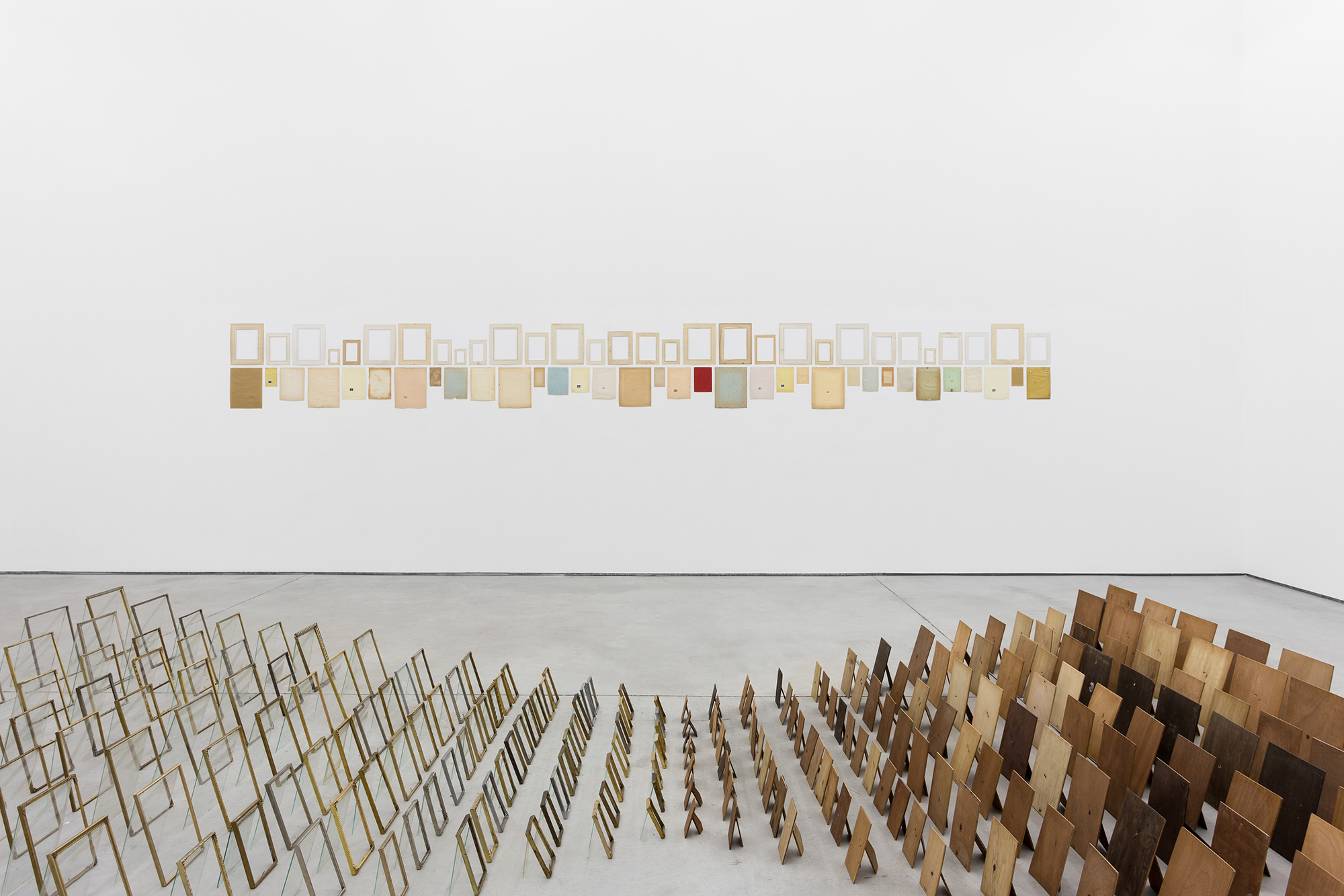

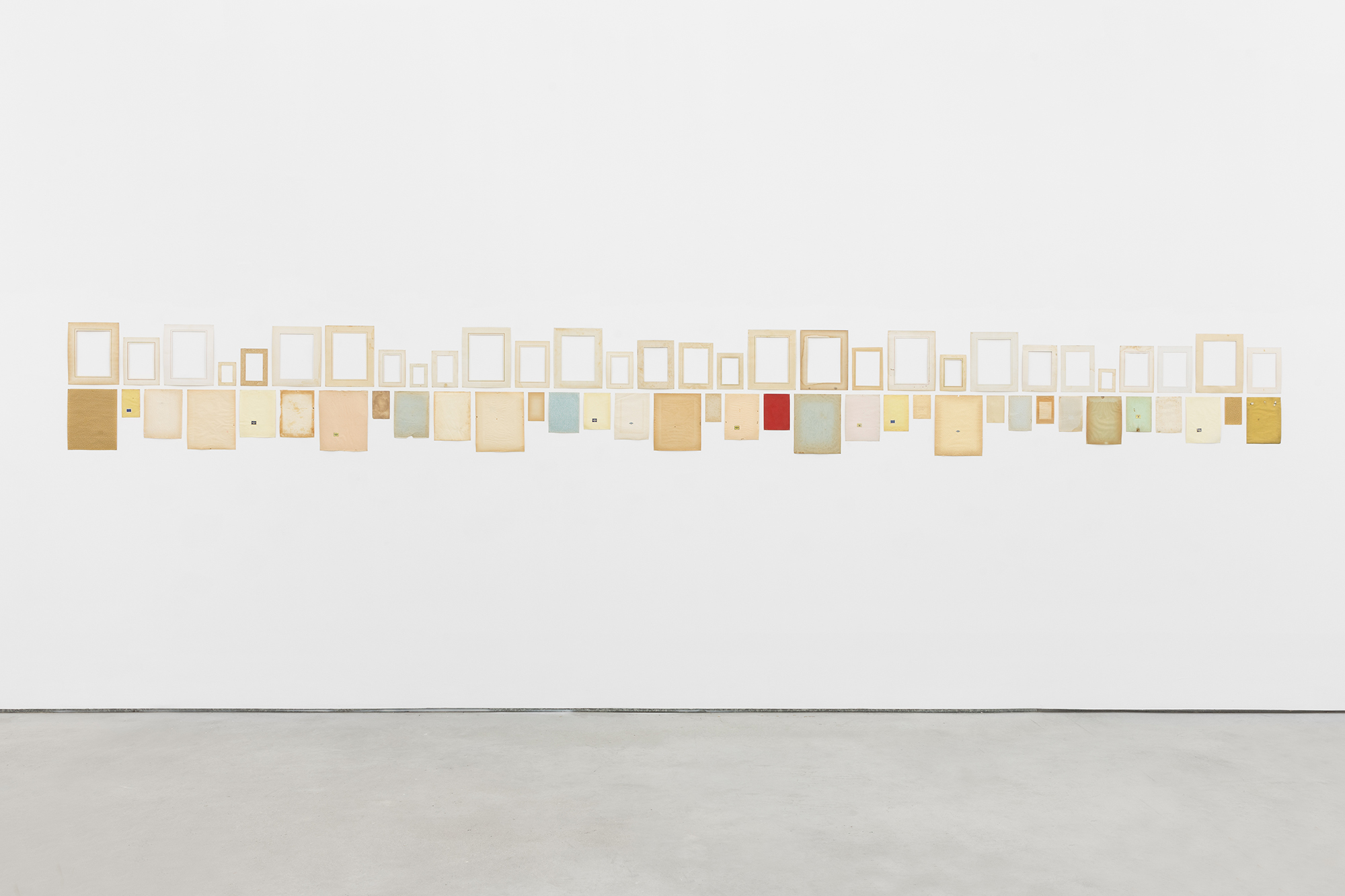

Depois de tudo ou mesmo antes de tudo é a ausência o que está, e o que condena. Mas é também a ausência que expande a memória da experiência, a certeza da passagem, a poesia inerente a esse vazio outrora habitado. A exposição desdobra-se, pois, nestes termos, em três – talvez mais – ausências, com diferentes origens, âmbitos e sentidos; cria-se uma rede, uma paisagem. De um modo mais específico, as peças são, elas mesmas, lugares vazios passíveis de acolher, de forma mais ou menos direta, de forma mais ou menos óbvia, a presença humana. No caso das fotografias do Tibete trata-se da ausência do autor ele mesmo, dada a distância temporal que o separa hoje, com quarenta e sete anos, dessa viagem; mas também de um contexto natural que poderia muito bem representar o mundo, antes – ou depois – do (de um) homem, ou qualquer lugar distante que julgamos que existe – certamente existe -, repetidamente, planeta afora, aguardando o viajante. O que é certo é que a experiência (e aqui serve-nos de luz a vertente iniciática daquela viagem) é algo de profundamente humano, profundamente pessoal e, por isso, absolutamente silencioso. A compreensão da experiência está muito mais próxima da observação do que do ditado. E, por isso, é que a memória é tão plástica e se projeta, pelas mãos do artista, de forma tão simples e em tão poucos gestos. Veja-se Paisagem para Desaparecidos I. Na peça, a ausência de matéria acessória, acrescentada, a avolumar-se sobre os objetos expostos, confere-lhe a leitura que vai direita ao assunto, que expõe, precisamente e em absoluto, o que não está; o que se extrema, mais ainda, em Paisagem para Desaparecidos III; que como num desvario, na obsessão pelo desvelamento, expõe a mesma evidência: cinzas. Ou poesia: a vida como um misto de fatalidade e salvação, e a beleza dentro dela: os encontros.

Rui Calçada Bastos tem uma relação muito particular com a viagem e, bem assim, com os vestígios de quaisquer passagens. Num sentido simbólico, ele concebe esta exposição como uma suspensão, como se nos fosse concedido o privilégio de flutuar entre memórias, sem sermos arrastados pelo curso infalível do tempo, mesmo compreendendo a impossibilidade de tais circunstâncias. Trata-se, um pouco como na sua viagem, de uma experiência mística, aquela que nos põe simultaneamente diante da fatalidade e da poesia.

Maria Joana Vilela

This exhibition starts in 1991. At age twenty, Rui Calçada Bastos (Lisbon, 1971) goes on an initiatory trip to Tibet. Walking 140km in nine days, he crosses the Indian Himalaya into a new life. Out of this episode emerged some of the pieces (Landscape for The Vanished II) shown today, which have come together with others so that different times and chronologies compose a landscape. And if the exhibition was conceived for today, it is because today condenses an entire time that evaporates as it moves along at its own cadence, while acquiring a mysterious density. Landscape for the Vanished is about absence.

Before everything, or even after everything, absence is what is there. But absence also expands the memory of experience, the certainty of transience, the poetry inherent to that once-inhabited void. The exhibition unfolds according to three absences – perhaps more – with different origins, scopes and meanings: a network is created, a landscape. More specifically, the pieces are in themselves empty places capable of hosting, more or less indirectly, more or less obviously, the human presence. The Tibet photographs deal with the absence of the author himself, given the temporal difference separating him now, at age forty-seven, from the trip; but they also depict a natural context, which could very well be a representation of the world before – or after – (a) man, or even any far-flung place we might suppose exists – and it certainly does –, repeatedly, somewhere on the planet, awaiting the traveller. Experience (particularly under the light of the trip’s initiatory dimension) is a deeply human, deeply personal thing, and, therefore, it is absolutely silent. The understanding of experience is much closer to observation than to imposition. For that reason, memory is highly plastic, projecting, at the artist’s hands, so simply and in such few gestures. Indeed, such is the case of Landscape for the Vanished I. In the piece, the absence of accessory, added matter, growing over the objects, as it were, affords a reading that goes straight to the point, exposing, precisely and absolutely, what is not there. This becomes even more extreme in Landscape for the Vanished III, in which a sort of obsessional un-concealment exposes the same evidence: ashes. Or poetry: life as a concoction of fate and salvation, and the beauty of it: the encounters it offers.

Rui Calçada Bastos’ relationship with travelling is very particular, and the same is valid for the all traces of transit. In a symbolic sense, he conceived this exhibition has a suspension, as if we were granted the privilege of floating in between memories without being dragged in by the infallible course of time, even while understanding the impossibility of such circumstances. To draw a parallel with his trip, this could be a mystical experience, as we are confronted simultaneously with fate and poetry.

Maria Joana Vilela